|

| April 21, 2020 | Volume 16 Issue 15 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

50 Years Ago: Apollo 13 averts disaster

Left: Apollo 13 crew of (left to right) Lovell, Swigert, and Haise (the photograph was actually taken after the flight due to the late replacement of Mattingly with Swigert). Right: The Apollo 13 crew patch with the motto indicating the increased emphasis on science.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the extra-long version. If you are pressed for time, you may want to consider watching the video in the middle of the article. It includes interview material with crew Commander James (Jim) Lovell Jr., which is material that is not in the article.]

By John Uri, NASA Johnson Space Center

The schedule for Apollo 13, the planned third Moon landing mission aiming for a pinpoint touchdown in the Fra Mauro highlands, was on track for the April 11, 1970, liftoff from Kennedy Space Center's (KSC) Launch Pad 39A.

Two days before launch, however, mission managers decided to replace prime Command Module Pilot (CMP) Thomas K. "Ken" Mattingly with his backup John L. "Jack" Swigert because Mattingly had been exposed to German measles, to which he had no natural immunity. Backup Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Charles M. Duke contracted the rubella virus that causes German measles from his son's three-year-old friend, thereby exposing the rest of the crew. Prime crew Commander James A. Lovell and LMP Fred W. Haise as well as backup Commander John W. Young and CMP Swigert all had natural immunity to the disease. Swigert completed several days of last-minute refresher training and integrated well with Lovell and Haise as the new crew of Apollo 13.

The weather, which caused such a problem during the launch of Apollo 12 the previous November, continued to be favorable for Apollo 13's liftoff and for the approximately 100,000 spectators who waited on nearby beaches to see the launch.

Suited up, Apollo 13 astronauts (front to back) Lovell, Swigert, and Haise walk toward the transfer van.

Liftoff came precisely at 2:13 PM EST on April 11, 1970. Engineers in Firing Room 1 handed over control of the flight to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, as soon as the rocket cleared the launch tower. Fully fueled, the Apollo 13 Saturn V was the heaviest space vehicle yet. At 6,501,733 pounds, about 25,600 pounds heavier than Apollo 12, and with the thrust of Apollo 13's first stage engines rated about 100,000 pounds lower in performance although still within specifications, it took the Saturn V between one-half and three-quarters of a second longer to clear the tower. In MCC, the Maroon Team led by Lead Flight Director Milton L. Windler took over control of the mission. The Capcom, or capsule communicator, the astronaut in MCC who spoke directly with the crew, during launch was Joseph P. Kerwin. Sitting beside Kerwin at the Capcom console was Mattingly who had flown back from Florida after being grounded. When he entered the control room, Windler greeted him saying, "Sorry to see you here, Ken."

Two minutes and 40 seconds after liftoff and at an altitude of about 42 miles, the Saturn V's first stage shut off as planned and the now empty stage was jettisoned. A few seconds later, the second stage's five J-2 engines ignited, followed by the jettison of the Launch Escape Tower, no longer needed to save the crew in case of a launch vehicle emergency. Five minutes and 32 seconds after liftoff, the second stage's center engine suddenly cut off more than two minutes earlier than planned.

Sequence of photographs of the launch of Apollo 13.

The problem was later identified as excessive longitudinal oscillations, the so-called Pogo effect, that had plagued early Saturn V launches, causing the engine controller to shut the engine off to prevent a more serious event. To compensate for the lost thrust from the center engine, the other four burned for an additional 34 seconds, and once the third stage ignited it too burned an extra nine seconds, resulting in Apollo 13 entering a 114-by-115-mile Earth orbit, very close to the plan. For Lovell, this was a record-setting fourth space mission, and he became the first person to ride a Saturn V into space twice. After a discussion with Kerwin about the second-stage engine problem, Lovell commented, "There's nothing like an interesting launch."

One hour and 48 minutes after liftoff, Kerwin called up to Apollo 13, "And you are Go for TLI," and at 2 hours and 35 minutes, the S-IVB's J-2 engine ignited for nearly 6 minutes to increase Apollo 13's velocity to 24,247 miles per hour, fast enough to escape Earth's gravity well and send the spacecraft and its crew toward the Moon. The next major event, the separation of the Command and Service Module (CSM) Odyssey from the S-IVB stage, took place about 25 minutes later, by which point Apollo 13 had reached an altitude of more than 4,300 miles.

In a maneuver now familiar on lunar voyages, Swigert turned Odyssey around and slowly guided it to a docking with the Lunar Module (LM) Aquarius still attached to the top of the S-IVB. The crew provided excellent TV images of the maneuver to Mission Control and to viewers on the ground, causing Kerwin to comment, "We've got a groovy TV picture." After the docking, the crew pressurized Aquarius before Swigert backed away from the third stage, extracting the LM in the process, and completing the Transposition and Docking maneuver. The S-IVB completed an 80-second evasive maneuver using its thrusters, but unlike previous missions where the spent third stage departed into solar orbit, Apollo 13 sent its stage on a trajectory to impact the Moon. The seismometer left behind by the Apollo 12 crew about 84 miles from the impact site picked up the resulting vibrations, lasting 3 hours and 20 minutes, providing scientists with clues about the Moon's interior.

Apollo 13 had now reached an altitude of more than 14,000 miles, and its velocity had slowed to 11,300 miles per hour as Earth's gravity continued its tug on the spacecraft. The crew placed the spacecraft into the Passive Thermal Control (PTC) or "barbecue mode," a slow rotation designed to equalize temperature extremes. In Mission Control, the Gold Team of Flight Director Gerald D. "Gerry" Griffin came on shift, and astronaut Vance D. Brand replaced Kerwin as Capcom.

Four images of the receding Earth as seen from Apollo 13, from a series of 11 photographs taken during the mission's first day in space.

The crew completed some housekeeping chores, ate dinner, and settled in for their first night's sleep in space. After a very long day, they had already reached a distance of nearly 73,000 miles from Earth.

By the time the crew awoke for their second day in space, Apollo 13 had reached a distance of 115,000 miles from Earth. As part of the daily news briefing to the crew, Kerwin reported on the breakup of The Beatles. And when reminding the astronauts that April 15, Income Tax Day, was approaching, Swigert sheepishly confessed that in the excitement of being added to the crew he had forgotten to file his taxes!

At 27 hours 21 minutes, Apollo 13 passed the halfway point in distance between the Earth and the Moon. Other than routine navigation sightings and housekeeping, the primary task for this day involved a mid-course correction. The TLI precisely placed them into a so-called free-return trajectory, meaning that if for some reason the Service Module's (SM) main engine failed to ignite to place them into lunar orbit, the spacecraft would loop around the Moon and head directly back to Earth without any major course corrections.

But the free-return trajectory limited the areas that astronauts could visit on the lunar surface, and Apollo 13's more scientifically interesting landing in the Fra Mauro highlands required a maneuver to leave the free-return path and enter into a so-called hybrid trajectory. That trajectory entailed a slightly higher risk should the SM engine fail, with the spacecraft missing Earth by about 40,000 miles, requiring a large course correction to assure a safe return. Just before the hybrid transfer mid-course correction maneuver, the astronauts turned on the TV camera and showed viewers an image of the growing Moon and then a spray of bright little stars as they conducted a water dump from the spacecraft, the water instantly freezing as it hit the vacuum of space.

They completed the hybrid transfer maneuver, a 6-second firing of the SM's Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine, without any issues and continued to send TV views of themselves inside the cabin. The burn reduced their closest approach point to the Moon from 290 to 69 miles. Late in the day, Haise called to Mission Control, "Are the flowers blooming yet?" prompting this response from Capcom Brand, "Gee, I haven't seen any." The coded exchange referred to Haise asking whether Mattingly had developed the German measles yet, and Brand confirming that so far the original Apollo 13 CMP remained healthy. Soon thereafter, the astronauts began their second rest period of the mission, at a distance of about 160,000 miles from the Earth.

From the TV transmission on Flight Day 2. Left: The Moon and a water dump. Middle: Haise (left) and Lovell inside the CM Odyssey. Right: Swigert inside the CM Odyssey.

Lovell, Swigert, and Haise awoke on the third day of their mission with Capcom Kerwin calling up that their "spacecraft is in real good shape as far as we're concerned. We're bored to tears down here." The only minor concern raised was that the pressure sensor on the SM's oxygen tank number 2 read off-scale high, but everyone assumed it was a sensor problem since the reading was normal earlier in the day until Swigert turned on the fan to stir the cryogenic oxygen. An attempt to restore the sensor by stirring the cryogenic oxygen in tank number 2 yielded no positive results, but controllers wanted to monitor it more closely and advised the crew to perform frequent stirs.

Mission planners decided that since their trajectory was so precise, a planned mid-course correction that day would not be needed, and instead the astronauts could move up their first familiarization of the LM Aquarius by three hours. After opening the hatch, first Haise then Lovell floated through the tunnel and into the LM. The astronauts broadcast their activities to the ground, taking viewers on a tour of Aquarius and Odyssey, with Haise demonstrating the drink bags inside their EMUs that were a new item on Apollo 13, providing hydration for the astronauts on the lunar surface.

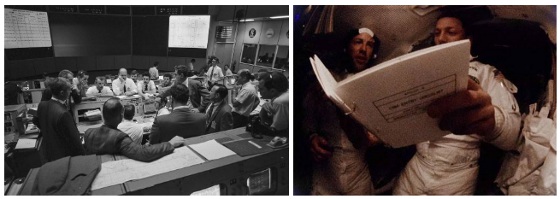

Flight Director Kranz (in foreground) watches the Flight Day 3 TV broadcast from Apollo 13 just minutes before the accident.

Following the end of the broadcast, Capcom Lousma called to the crew with a few housekeeping chores including stirring the cryogenic liquids in both oxygen tanks and both hydrogen tanks in the SM to homogenize the fluids to enable more accurate quantity readings. Shortly after, at 55 hours and 55 minutes into the flight, Swigert called down, "Houston, we've had a problem here."

Capsule communicator (Capcom) astronaut Jack R. Lousma asked, "This is Houston. Say again, please." Lovell replied, providing some more detail on their condition, "Ah, Houston, we've had a problem here. We've had a Main B Bus Undervolt." Lovell reported that sensors picked up a drop in voltage across one of the two main DC electrical buses supplying power to the Command and Service Module (CSM), triggering the warning lights to alert the crew to the problem.

At this point, neither the crew nor the team in Mission Control knew the cause of the problem. Because the voltage on Bus B had come back to normal, everyone's first inclination was to blame instrumentation or some unknown transient event. But Haise, having left Aquarius and now back in Odyssey, radioed down that despite the now normal voltages, there was "a pretty large bang associated with the Caution and Warning there."

VIDEO: The Apollo 13 mission has become known as "a successful failure" that saw the safe return of its crew Commander James (Jim) Lovell Jr., Command Module Pilot John Swigert Jr., and Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise Jr. [Credit: NASA]

The crew first suspected that something had happened to the LM, perhaps a micro-meteoroid strike, and Lovell and Swigert rushed to close the hatch to isolate the two spacecraft. Haise noted that the quantity sensor for oxygen tank 2, which had failed earlier in the mission by showing off-scale high and located in the same tank that had experienced anomalies during the Countdown Demonstration Test back in March, was now oscillating between 20% and 60%, perhaps rocked back to life by the jolt.

The crew suddenly faced a cascade of malfunctions. First Lovell noted that sensors in the helium tanks used to pressurize the SM's Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters were showing alarms as were some of the propellant systems. The DC Main B Bus that showed normal just a few minutes before now showed zero volts, the Alternating Current (AC) bus 2 read zero, and the DC Main A Bus showed an undervolt, meaning instead of the normal 27 volts it was reading 25.5 volts. Two of the three fuel cells (FCs) that combined oxygen with hydrogen to supply power to the DC busses appeared to be offline, explaining why Main Bus B showed zero volts as it received power from FC 3 and why Main Bus A's voltage was dropping because it drew power from FC 1 and 2 and FC 1 was offline.

Haise attempted to reconnect the fuel cells to get the busses back up, but neither FC 1 nor FC 3 appeared to be operational. In Mission Control, the team was trying to ascertain if they were dealing with an instrumentation issue or if there was a real problem. Five minutes had elapsed since the crew heard the bang.

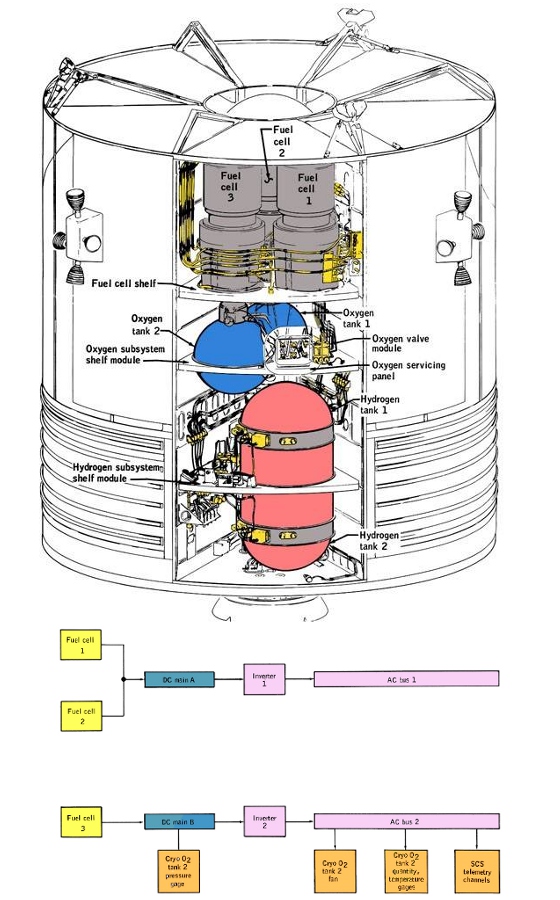

Top: Schematic of the SM tanks and fuel cells. Bottom: Schematic of the SM Electrical Power System at the time of the accident.

About 14 minutes after the incident began, Lovell called down to say that the quantity in oxygen tank number 2 now read zero, and even more worrisome, "It looks to me, looking out the hatch, that we are venting something. We are venting something out into space. It's a gas of some sort." The venting couldn't be just instrumentation.

Kranz got on the internal Mission Control loop to talk to his controllers with some of the most memorable words spoken in human spaceflight: "Okay now, let's everybody keep cool, we got the LM still attached, the LM spacecraft's good so if we need ... to get back home we've got a LM to do a good portion of it with. Okay, let's make sure that we don't do anything that's going to blow our CSM electrical power with the batteries or that will cause us to lose the main or the fuel cell number 2. Okay, we want to keep the O2 and that kind of stuff working. We'd like to have RCS, but we got the Command Module system, so we're in good shape if we need to get home. Let's solve the problem, but let's not make it any worse by guessing."

Fifteen minutes had elapsed since the crew heard the bang.

To Mission Control and the crew onboard Apollo 13, several things were becoming clear even as the underlying cause remained unknown. The CSM was losing oxygen required for the crew to breathe and to generate power in the fuel cells. Mission Control estimated that at the rate the quantity was decreasing in oxygen tank 1 they had less than two hours of power generation remaining. The LM appeared unaffected, and the idea of using it as a lifeboat started to be discussed. The continued venting caused the SM's RCS thrusters to fire to try to maintain the spacecraft's attitude, important to maintain good communications. With FC 1 and FC 3 off line, the crew wanted to preserve FC 2 as long as possible. Haise called down to Mission Control that it might be a good idea to think about the consumables available in the LM, even though it could support two crewmembers for two days and now it would have to support three crewmembers for four days. Critical consumables included oxygen for the crew, power to run the spacecraft's systems including the navigation and life support equipment, water both for drinking and to cool the electronic equipment, and carbon dioxide removal.

Of immediate urgency, the crew needed to preserve enough consumables such as electricity and oxygen in the CM to allow for a successful reentry and splashdown at the end of the mission. The two sources of oxygen in the CM were a surge tank and a repress package, the latter a set of three tanks used to repressurize the cabin in case it had to be vented -- the crew needed to isolate the surge tank to ensure it retained sufficient oxygen for them to breathe during reentry. Thinking the leak might be coming from FC 3, Mission Control asked the crew to shut it down -- the action ruling out a Moon landing since flight rules stated the spacecraft cannot enter lunar orbit with only two working fuel cells. Shutting down FC 3 had no effect on stopping the leak because the problem was not with any of the fuel cells but with the tanks supplying oxygen to all three of them -- tank 2 was empty and tank 1 getting there.

Less than an hour after the crew heard the bang, Flight Director Kranz instructed his team that the new mission plan involved abandoning the Moon landing, looping around the Moon, and getting the crew home safely as quickly as possible. The first order of business was getting back onto a free-return trajectory. A course correction on the mission's second day specifically maneuvered Apollo 13 from such a path onto a hybrid trajectory to enable the landing at Fra Mauro. With the landing off the table, they needed to make another course correction to maneuver back to the free return path. Kranz knew that the SM's Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine could not be used, so he ordered his team to prepare plans to use the LM's Descent Propulsion System (DPS) engine, normally used to land on the Moon, to perform the maneuver. Fortunately, engineers had previously drawn up contingency plans to use the DPS to maneuver the docked spacecraft in case of an SPS failure.

His shift over, Kranz handed Mission Control over to Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney and his Black Team of controllers with Lousma staying on as Capcom. Normally, the team going off-shift would go home for much needed rest, but this night they stayed and pored over all the available data to understand what happened aboard Apollo 13. Lunney began directing his team to come up with procedures to activate the LM Aquarius as quickly as possible to ensure that its communications, navigation, and life support systems were all functioning before the CM Odyssey had to be shut down. Lousma called up to the crew that as the quantity in tank 1 "was slowly going down to zero, ... we're starting to think about the LM lifeboat." Ninety minutes had elapsed since the crisis began.

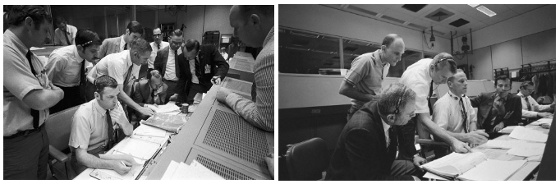

Left: Flight Director Lunney (seated) shortly after the accident. Right: Capcom Lousma (seated in white shirt) assisted by (left to right) Slayton, Mattingly, Brand, and Young.

It was now a race to activate the LM and get all three crewmembers inside Aquarius -- Odyssey had just 15 minutes of power left. Haise, already in Aquarius, radioed to Lousma with the good news, "Jack, I got LM power on." He performed an abbreviated activation to get oxygen and water flowing, and the electrical, navigation, and communications systems enabled. One unexpected communications issue arose -- the LM used the same frequency as the spent S-IVB stage, on its way toward an impact with the Moon. Under normal circumstances, this interference would not have occurred since the stage would have crashed before the crew activated the LM. Meanwhile, back in Odyssey Swigert busied himself with deactivating that spacecraft, completing the task less than three hours after the crisis began.

With the immediate crisis of finding the crew a safe haven over, Lunney addressed his team concerning the major issues they all faced -- the maneuvers needed to get them home as quickly and safely as possible; reducing power usage in the LM to ensure its batteries lasted as long as possible; and assessing the onboard consumables especially carbon dioxide removal. During a midnight press conference, Deputy Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center Christopher C. Kraft, James A. McDivitt, Apollo Spacecraft Program Office Manager, and Sigurd A. "Sig" Sjoberg, Director of Flight Operations, provided reporters with a status of the problems with Apollo 13, with Kraft describing it "as serious situation as we've ever had in manned spaceflight." The managers expressed confidence that the crew would return safely to Earth, although McDivitt added, in comparing the current crisis to the Gemini 8 accident in 1966, that that crew was able to return to Earth in 20 minutes while Apollo 13 had many hours to go.

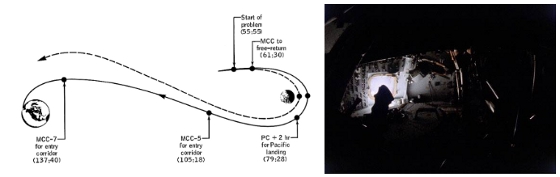

Left: Apollo 13's trajectory before and after the accident. Right: Darkened CM after its shutdown, the only light coming from the Sun shining through the windows.

At 61 hours 30 minutes into the mission, at a distance of 216,626 miles and about five and a half hours after the accident, the astronauts conducted a 34-second firing of the LM's DPS engine to put the spacecraft back onto a free-return trajectory. The maneuver raised the altitude of their closest pass around the back side of the Moon from 69 miles to 156 miles. If the crew did nothing else, on this trajectory they would splash down in the Indian Ocean at about 151 hours and 45 minutes. This was not an optimal scenario since the prime recovery ship, the USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2), was stationed in the Pacific Ocean and Mission Control wanted them home sooner to ensure adequate consumables remained. A second maneuver after they rounded the Moon, called PC+2 for two hours after pericynthion or closest point to the Moon, would speed up their return and move the landing zone into the Pacific Ocean.

In Mission Control, Joseph P. Kerwin took over the Capcom position from Lousma, and Flight Director Gerald D. "Gerry" Griffin's Gold Team took their seats at their consoles. For a short time, backup Lunar Module Pilot Charles M. Duke, recovered from his bout of German measles, took over the Capcom position, followed by Vance D. Brand. For the next few hours as the astronauts continued to approach the Moon, they continued conserving power in Aquarius and making preparations for the PC+2 burn. Kerwin advised them to move the lithium hydroxide canisters, used to scrub the cabin's atmosphere of carbon dioxide (CO2), from Odyssey to Aquarius. A buildup of condensate in the cold CM cabin could render the canisters unusable. The crew entered a rest period, although sleep was understandably hard to come by. Shortly before Apollo 13 entered the Moon's shadow, Kranz's White Team of controllers arrived back in MCC to take their consoles, just 18 hours after the accident.

Three images from Apollo 13 as they round the far side of the Moon. Left: Keeler Crater. Middle: Tsiolkovsky Crater. Right: Mare Muscoviense.

At 76 hours 42 minutes, Apollo 13 entered the Moon's shadow, and the astronauts could now see stars that had been obscured by the cloud of debris following the spacecraft. Precisely on schedule, 26 minutes later and continuing to accelerate as the Moon's gravity pulled them on, Apollo 13 disappeared behind the Moon and communications stopped. While behind the Moon, the crew of Apollo 13 set a record that stands to this day as the most distant human space travelers. Because the Moon was farther in its elliptical orbit around the Earth than during other Apollo missions and because Apollo 13's closest approach was farther from the Moon than other missions, Lovell, Swigert, and Haise hold the distance record of 248,655 miles. For Lovell, this was his second time seeing the Moon up close, but for Swigert and Haise this was their single opportunity to peer down at Earth's satellite. Like tourists anywhere, they took a number of spectacular photographs -- especially of features on the far side.

Precisely 25 minutes after disappearing behind the Moon, Apollo 13 reappeared on the other side, with Lovell greeting Mission Control, "Good morning, Houston. How do you read?" As they departed the Moon, the astronauts snapped a few more photographs including the area of the Apollo 11 landing site, the Sea of Tranquility. Thirty minutes later, Brand informed the crew that the S-IVB stage had impacted the Moon and Apollo 12's seismometer recorded the event from 85 miles away, prompting Lovell to wryly respond, "Well, at least something worked on this flight." Haise added, "I'm sure glad we didn't have a LM impact too," a reference to the planned impact of the LM's ascent stage after he and Lovell had returned from the Moon.

An hour and a half later, with the Moon now more than 6,200 miles behind them, the astronauts fired the LM's DPS engine for 4 minutes and 24 seconds to accelerate the spacecraft and return them to Earth 10 hours earlier and in the Pacific Ocean. Mission Control filled with many astronauts and managers, including NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine, to observe the PC+2 maneuver. After completing the burn, the astronauts powered down Aquarius to conserve the spacecraft's batteries. One unpleasant side effect of the LM power down along with the total shutdown on the CM was cabin temperatures dropping to uncomfortable levels without the electronic equipment generating heat, making sleep more difficult.

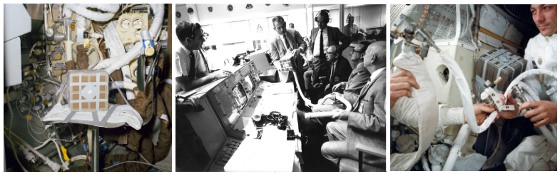

Left: Setup to use CM LiOH canisters in the LM during an altitude chamber test. Middle: Slayton demonstrating CM LiOH canister setup to managers in Mission Control. Right: Swigert (right) and Lovell assembling the CM LiOH setup in the LM Aquarius.

The next order of business involved rigging up a system to use the LiOH canisters from Odyssey that are square in shape with the system in Aquarius that uses round canisters. This provided the crew with adequate CO2 removal for the remainder of the flight. Brand informed the astronauts that a team was working on a procedure to solve this "square peg in a round hole" problem. Indeed, a team led by Robert E. "Ed" Smylie, Chief of the Crew Systems Division, his Deputy James V. Correale, and Test Director James C. "Jim" LeBlanc did exactly that, using only replicas of items the crew had on board. The setup involved using a spacesuit's liquid cooled garment and inlet hose, plastic bags, a cue card from the flight plan, and of course duct tape to attach the CM canister to the LM's outlet hose to pass air through to scrub the CO2. The engineers tested the setup in an altitude chamber and Capcom Kerwin called the procedure up to the crew. Swigert and Lovell built two of the makeshift contraptions, and within minutes after the astronauts installed the first one in Aquarius, CO2 levels dropped significantly.

Left: Lovell (left) and Swigert eating in the LM during the Earthward coast. Right: Haise in the LM during the Earthward coast.

Brand called up to the astronauts about the status of their consumables, and all looked adequate to get them home safely. To reassure them further, Chief of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. "Deke" Slayton got on the Capcom loop, and knowing they hadn't had much sleep since well before the accident, advised them, "We think you guys are in great shape, all the way around. Why don't you quit worrying and go to sleep." Lovell responded, "Well, I think we just might do that -- or part of us will," a reference to the fact that one astronaut stayed awake on watch duty at all times since the accident. He and Swigert slept for about five hours in Odyssey with Haise keeping watch in Aquarius. After that exchange, Lousma relieved Brand on the Capcom console while Flight Director Windler's Maroon Team of controllers took their respective consoles.

The astronauts put the spacecraft in a Passive Thermal Control (PTC) or barbecue mode, rotating about once every 11 minutes along the longitudinal axis to evenly distribute temperatures. The spacecraft experienced a slight wobble, likely due to venting from one of the SM's hydrogen tanks as they heated up during the sunlit part of the PTC rotation. Lunney's Black Team of controllers came on to relieve Windler's engineers, and Kerwin came back in to replace Lousma at the Capcom console. At 90 hours and 25 minutes, at a distance of 216, 277 miles, Apollo 13 passed from the Moon's gravitational field back into the Earth's and slowly began to accelerate toward its home planet.

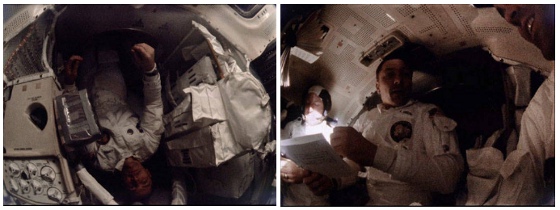

Left: Swigert entering the LM Aquarius through the docking tunnel. Right: Haise in the LM Aquarius making notes on a checklist.

Kerwin and Swigert spent some time to properly configure all 417 switches and circuit breakers in Odyssey in preparation for a brief partial activation to check on its systems and also for the eventual reactivation for reentry. Swigert returned to the dark CM and verified that both main busses operated properly, a good sign since they were needed for reentry. Shortly after Brand replaced Kerwin as Capcom at about 97 hours, Haise reported hearing a thump in the LM's descent stage, followed by a "shower of snowflakes."

Unbeknownst to the crew and Mission Control, battery number 2 (of four) in the descent stage experienced a short circuit, with a potentially dangerous release of oxygen and hydrogen gas. Two hours later, the crewmembers reported a warning alarm regarding battery 2, and Mission Control, with Griffin's Gold Team having relieved Lunney's Black Team, advised them to turn it off only to reverse the decision a few hours later, not fully understanding the problem. Swigert returned to Odyssey and powered it up briefly so Mission Control could receive enough telemetry to check on the status of its systems. They all appeared to be working well, especially given the cold temperatures, a positive sign for when they powered the capsule up for entry.

For the next few hours, the astronauts prepared themselves for the next maneuver -- again to be conducted using the LM's DPS engine -- but without using the LM's computer to conserve power and cooling water, they would have to maintain the spacecraft's attitude using visual sightings of the Earth and Sun out the windows. Lousma had returned to the Capcom console to help the crew with the maneuver. At 105 hours and 18 minutes into the flight, and still 175,000 miles from Earth, the astronauts ignited the LM's DPS engine for 14.8 seconds. The burn had the desired effect of fine-tuning their reentry path into the Earth's atmosphere. Windler and his Maroon Team resumed their positions in MCC, replacing Griffin's Gold Team. With about 38 hours remaining in the perilous journey, Lovell took over the watch aboard Apollo 13.

Although Mission Control wanted Swigert and Haise to get some sleep while Lovell kept watch, all three crewmembers stayed awake and continued working. Lousma informed them that the status of all their consumables appeared sufficient to last the remainder of the mission, some with very comfortable margins, with the partial powerdown of Aquarius contributing significantly to power and cooling water margins. Eventually, Haise went to sleep in the tunnel between the two spacecraft with his head resting on the LM's ascent engine cover and Swigert on the floor of the LM. While Lovell kept watch, Lousma walked him through the planning activities ongoing in Mission Control, including a possible final midcourse correction about five hours before entry, the charging of two of Odyssey's three batteries from Aquarius (a procedure never done before but essentially just reversing one in which the CM supplies power to the LM on its initial activation), reactivating the CM, and the sequence for jettisoning first the Service Module (SM) and finally the LM just prior to reentry.

Shortly after the astronauts began the 15-hour recharge of Odyssey's batteries, Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney and his Black Team of controllers relieved Windler's team and Joseph P. Kerwin replaced Lousma as Capcom. Swigert and Haise ended their short sleep periods and Lovell took a turn at resting, but was back up within two hours. Due to cold cabin temperatures, about 51 degrees F in Aquarius and in the 40s in Odyssey, Lovell reported to Kerwin that he and Haise used the lunar surface overshoes to keep their feet warm and donned two pairs of underwear. Back in Houston, Chief of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. "Deke" Slayton and Apollo 11 Commander Neil A. Armstrong gave separate press conferences to update the media on the flight of Apollo 13.

With all three crewmembers awake, Kerwin read up to them the overall flow of events for the last six and a half hours of their mission, beginning with activating and warming up the CM's Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters followed by activating the LM's systems to prepare for the final midcourse correction maneuver using the LM's RCS thrusters. From that position, they would jettison the SM and try to obtain some photographs that might show the damage from the oxygen tank explosion. About two hours prior to entry, they would reactivate the CM which had been in a dormant state for four days, one hour later jettison the LM, and begin preparations for reentry into the Earth's atmosphere. After that long conversation, the Gold Team of Flight Director Gerald D. "Gerry" Griffin relieved Lunney's engineers, and Vance D. Brand relieved Kerwin at the Capcom console. Brand's first order of business was to send up to the crew the CM stowage plan including which items to transfer to the LM and what things to bring in from the LM prior to separation, including the astronauts themselves! Proper stowage was essential because mass distribution affected the aerodynamic performance of the CM.

Left: An impromptu meeting around the Flight Director's console to discuss reentry procedures. Right: Lovell (left) and Swigert reviewing the entry checklist.

When it was time to read up the complex new procedures to reactivate the CM and separate the SM, astronaut Thomas K. "Ken" Mattingly took over the Capcom duties. Mattingly, the original Apollo 13 CMP grounded two days before launch due to concerns over his exposure to German measles, had spent hours in the CM simulator finalizing the procedures. Mattingly did not contract the infectious disease and had put his talents to work to help recover his fellow astronauts. Brand then read up the procedure for the LM deactivation and jettison to Haise.

Aboard Apollo 13, now 86,000 miles from Earth and continuing to accelerate, Lovell and Swigert tried to get some sleep while Haise took the watch, while in Mission Control Lousma relieved Brand at the Capcom console and avoided calls to the crew to allow Haise to rest as well. The increasingly cold temperatures made sleep difficult, and Haise began to experience chills, the first symptoms of his developing urinary tract infection likely caused by dehydration. To help warm the spacecraft and make the crew more comfortable, Mission Control gave the GO to activate the LM three hours early and orient it so it received more sunlight through its windows. Flight Director Eugene F. "Gene" Kranz and his White Team of controllers took their consoles about eight hours before entry, relieving Griffin's team, and planned to monitor the mission all the way to splashdown. Kerwin replaced Lousma at the Capcom position for the last hours of the mission.

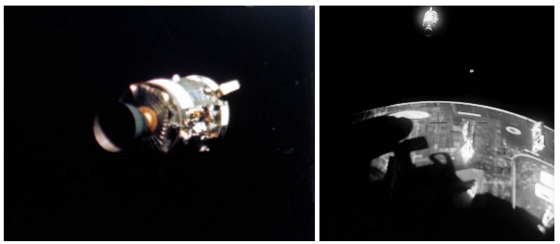

Left: View of the damaged SM shortly after the crew jettisoned it. Right: View of the departing SM, with the CM in the foreground and the Moon in the far distance.

With about six and a half hours to go in the flight of Apollo 13, Swigert entered Odyssey to begin the reactivation process. Using the LM's navigation system, Lovell began the process of aligning the docked spacecraft to perform the final mid-course maneuver of the mission to fine-tune the angle at which Apollo 13 entered the Earth's atmosphere. Five hours before entry and at a distance of 44,000 miles from Earth, the astronauts fired the LM's RCS thrusters for 23 seconds. Within one minute after the end of the successful burn, Lovell reoriented the spacecraft to prepare to jettison the SM that occurred 20 minutes later, at a distance of 41,049 miles from Earth. About two minutes later, the astronauts got their first view of the damaged SM, with Lovell exclaiming, "There's one whole side of that spacecraft missing. Right by the high gain antenna, the whole panel is blown out, almost from the base to the engine." Haise concurred, "It's really a mess."

Swigert continued activating Odyssey's systems, some running from one the CM's batteries with others still drawing power from Aquarius. At two and a half hours before entry, Mission Control gave Swigert the GO to activate all the CM's systems from the batteries as Haise terminated the power transfer from the LM. He then joined Swigert in Odyssey to assist with the activation. With direct communications reestablished with Odyssey, Mission Control updated the spacecraft's onboard computer and began monitoring its systems via telemetry, showing a cabin temperature of 38 degrees F!

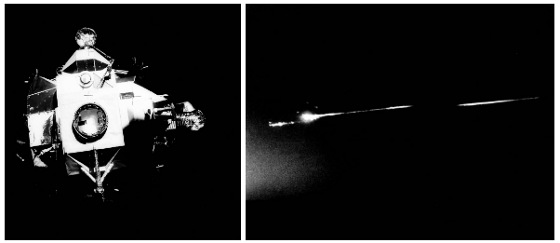

Left: View of the departing LM Aquarius shortly after the crew jettisoned it. Right: Photograph taken by an unidentified airline passenger of the LM and SM burning up on reentry.

The next task for the astronauts was the jettison of the LM Aquarius, the lifeboat that kept them safe for four days after the accident. Lovell essentially put Aquarius on autopilot, joined Swigert and Haise in Odyssey and closed the LM and CM hatches behind him. They partially depressurized the vestibule between the two spacecraft, using the remaining pressure as a propulsive force to send the LM on its way. At 141 hours and 30 minutes into the flight and at an altitude of 12,946 miles, they jettisoned the LM, prompting Capcom Kerwin to say, "Farewell, Aquarius, and we thank you." Both the SM and LM burned up on reentry, and an unidentified passenger aboard an Air New Zealand airliner en route from Fiji to Auckland captured an image of them streaking across the night sky.

Apollo 13 was now down to its final component, the CM Odyssey. The spacecraft continued to accelerate as it approached the Earth, and about an hour after saying farewell to the LM, it encountered the top layers of the planet's atmosphere, having reached a top velocity of 24,689 miles per hour. The contact with molecules in the upper atmosphere at such high speed caused them to be ionized, cutting off communications with the spacecraft for several minutes, a period known as the blackout. The rapid deceleration resulted in the astronauts experiencing a peak load of about 5.2 gs.

Left: Controllers in Mission Control watching the descent of Apollo 13. Right: Moment Apollo 13 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean.

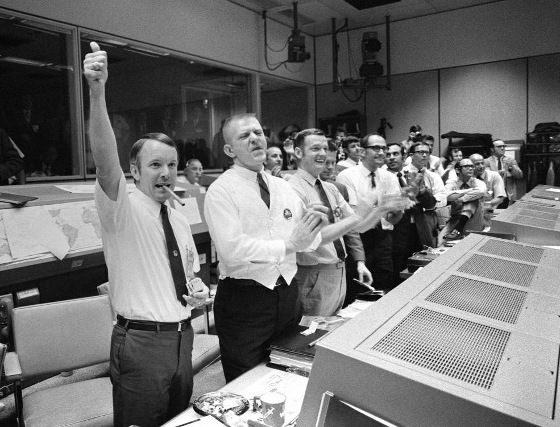

Coming out of the blackout, communications between Odyssey and Mission Control were restored. At an altitude of 24,000 feet, two drogue parachutes deployed to slow and stabilize the descending craft. At 10,000 feet, the three main orange-and-white parachutes opened to gently guide Odyssey to the Pacific waters, with splashdown occurring after a flight of 142 hours 54 minutes and 41 seconds. The splashdown point was about one mile from the predicted target and four miles from prime recovery ship the USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2). The crew of Apollo 13 had made it back to Earth safely. In Mission Control, pandemonium erupted as the exhausted flight controllers, joined by astronauts, managers, and VIPs, rejoiced in the successful conclusion of a very perilous mission.

Flight Directors (left to right) Griffin, Kranz, Lunney, and Windler cheering after the successful splashdown of Apollo 13.

The recovery team of US Navy Frogmen and sailors from the USS Iwo Jima recovered the astronauts and delivered them by helicopter to the deck of the carrier. The Iwo Jima's skipper, Captain Leland E. Kirkemo, and Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, Commanding Officer of Task Force 130 the Pacific Recovery Forces, welcomed them aboard the ship.

Left: Apollo 13 astronaut Lovell has just emerged from the CM as Haise (left) and Swigert watch from the recovery raft minutes after splashdown. Right: Apollo 13 astronauts (left to right) Haise, Lovell, and Swigert wave to sailors after exiting the recovery helicopter on the USS Iwo Jima.

After a brief welcoming ceremony, the astronauts were taken to the ship's sick bay for a brief medical checkup and telephone conversations with their families. President Richard M. Nixon telephoned to congratulate them on their successful recovery. About an hour later, the sailors brought Odyssey aboard the ship. The Apollo 13 postflight activities differed from those of the previous two Apollo missions in that the crew did not enter quarantine since they didn't land on the Moon, although all the pertinent facilities and personnel were deployed on the Iwo Jima.

EDITOR'S END NOTE: So in the end, what happened? Why was there a problem in the first place?

In the NASA video posted on this page, crew Commander James (Jim) Lovell Jr. said the Apollo 13 mission "was plagued by bad omens and bad luck from the very beginning." To explain the main cause of the explosion, he said, "Years before the flight, when the spacecraft was being built, a damaged liquid oxygen tank was installed in the spacecraft. The tank had been dropped on the factory floor." Lovell said a little piece of [damaged] plumbing prevented the normal procedure for removing oxygen. "It was a bomb waiting to go off," he said.

Published April 2020

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy